#84: OZU, Yasujiro: Good Morning (1959)

OZU, Yasujiro (Japan)

The Film

The Booklet

DVD: Four-page wraparound featuring an essay by Rick Prelinger.

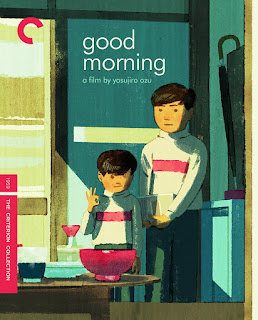

Blu-ray: 12-page wraparound. The first thing you notice are the gorgeous illustrations by Tatsura Kiuchi, on both the box and insert. The essay by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum is brilliant. For example:

I Was Born, But . . . (1932) {Eclipse Series 1}, Ozu’s silent comedy, with a 2008 score by Donald Sosin.

Video interview

Good Morning [1959]

Spine #84

DVD/Blu-ray

DVD/Blu-ray

2000 synopsis

Ozu's hilarious Technicolor re-working of his silent I Was Born, But . . ., Good Morning (Ohayo) is the story of two young boys in suburban Tokyo who take a vow of silence after their parents refuse to buy them a television set. Shot from the perspective of the petulant brothers, Good Morning is an enchantingly satirical portrait of family life that gives rise to gags about romance, gossip, and the consumerism of modern Japan.

93 minutes

Color

Monaural

in Japanese

1:33:1 aspect ratio

Criterion Release 2000

Color

Monaural

in Japanese

1:33:1 aspect ratio

Criterion Release 2000

2017 synopsis

A lighthearted take on director Yasujiro Ozu's perennial theme of the challenges of inter-generational relationships, Good Morning tells the story of two young boys who stop speaking in protest after their parents refuse to buy a television set. Ozu weaves a wealth of subtle gags through a family portrait as rich as those of his dramatic films, mocking the foibles of the adult world through the eyes of his child protagonists. Shot in stunning Technicolor and set in a suburb of Tokyo where housewives gossip about the neighbors' new washing machine and unemployed husbands look for work as door-to-door salesmen, this charming comedy refashions Ozu's own silent classic I Was Born, But . . . to gently satirize consumerism in postwar Japan.

94 minutes

Color

Color

Monaural

in Japanese

1:37:1 aspect ratio

Criterion Release 2017

Director/Writers

Ozu was 56 when he directed Good Morning.

Ozu was born in Tokyo on December 12, 1903. His father was a fertilizer salesman. He and his brothers — as was the custom in middle-class families at the time — were sent to the countryside to be educated. Ozu was a rebellious, undisciplined student. He matriculated no further than middle school, preferring his twin passions of watching American films and drinking. He rarely saw his father between 1913 and 1923, but forged a potent relationship with his loving mother — Ozu never married and lived with her until her death in 1962 at the age of 87. Ozu himself died just a year later — the day before his 60th birthday, December 11, 1963. Carved on his tombstone is a single Japanese character — mu — the Zen nothingness that is everything.

Ozu’s uncle got him his first job in the film industry as an assistant cameraman, which basically involved schlepping heavy cameras from place to place. He worked his way up to become an assistant director to the both now and then obscure Tadamoto Ôkubo, who “specialized in a kind of comedy which was called ‘nonsense-mono’" — a running series of gags held together boy a slight story line, a succession of chuckles intended to make the time pass.

Ozu was quite satisfied with the position. He could drink to his heart’s content (he was a heavy drinker, all his life) and had none of the responsibilities and worries that he quickly realized were the domain of the director.

Nevertheless, his friends urged him on and an incident (a waiter at the studio cafeteria insulted him) provoked him to overcome the inertia of his non-ambition. Besides, he had always loved film (almost all American — at his job interview, he admitted to having seen only three Japanese films!) and probably felt the confidence to strike out on his own.

Ozu directed 54 films between 1927 and 1962.

- Thirty-seven survive in an least abbreviated form.

- Thirty-five are silent, 19 talkies.

- Forty-eight are in B&W and six in color.

- By decade:

- 1921-1930: 19 films

- 1931-1940: 18 films

- 1941-1950: 6 films

- 1951-1960: 18 films

- 1961-1962: 2 films

- Of the 37 surviving films, 27 are available on DVD — 21 on The Criterion Collection or their budget label, Eclipse — but some of the earlier films are available only from Asia, and require a region-free DVD player (which are quite affordable these days). Naturally, the quality of the Criterion releases is extraordinary.

Ozu and fellow writer Noda stitched this thing together beautifully.

Other Ozu films in the Collection:

Eclipse Series 42: That Night's Wife (1930)

Eclipse Series 42: Walk Cheerfully (1930)

Eclipse Series 10: Tokyo Chorus (1931)

Eclipse Series 10: I Was Born, But . . . (1932)

Eclipse Series 42: Dragnet Girl (1933)

Eclipse Series 10: Passing Fancy (1933)

#232: A Story Of Floating Weeds (1934)

#525: The Only Son (1936)

#526: There Was A Father (1942)

#331: Late Spring (1949)

#240: Early Summer (1951)

#989: The Flavor Of Green Tea Over Rice (1952)

#217: Tokyo Story (1953)

Eclipse Series 3:Early Spring (1956)

Eclipse Series 3: Tokyo Twilight (1957)

Eclipse Series 3: Equinox Flower (1958)

#232: Floating Weeds (1959)

Eclipse Series 3: Late Autumn (1960)

Eclipse Series 3: End Of Summer (1961)

#446: An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

Eclipse Series 42: That Night's Wife (1930)

Eclipse Series 42: Walk Cheerfully (1930)

Eclipse Series 10: Tokyo Chorus (1931)

Eclipse Series 10: I Was Born, But . . . (1932)

Eclipse Series 42: Dragnet Girl (1933)

Eclipse Series 10: Passing Fancy (1933)

#232: A Story Of Floating Weeds (1934)

#525: The Only Son (1936)

#526: There Was A Father (1942)

#331: Late Spring (1949)

#240: Early Summer (1951)

#989: The Flavor Of Green Tea Over Rice (1952)

#217: Tokyo Story (1953)

Eclipse Series 3:Early Spring (1956)

Eclipse Series 3: Tokyo Twilight (1957)

Eclipse Series 3: Equinox Flower (1958)

#232: Floating Weeds (1959)

Eclipse Series 3: Late Autumn (1960)

Eclipse Series 3: End Of Summer (1961)

#446: An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

The Film

With his 24th film, in 1932 — I Was Born, But ..., Ozu had directed a big hit, both critically and commercially. Ozu’s main concern was the perception of life’s capricious unpredictability’s from the point of view of both the children and the adults.

Seen in that light, Good Morning is most certainly a sequel. In addition to the identical scenes of the boys refusing to speak, running away, etc., the idea of adult life from a child’s POV (and a bit of the reverse) is what makes this gorgeous film tick ...

- This was Criterion’s first Ozu release (2000). It was released on Blu-ray in 2017.

- Toshirô Mayuzumi’s fine score contributes much to this film. He captures the corny, contemporary sound Ozu liked (accordions, xylophones, jaunty tunes) combined with a serious orchestral palette. Check out the mischievous unexpected half-step modulation under the director’s credit!

Ozu uses the first 44 seconds to ease us into the action:

- Two transmission towers; in the background, behind a long white picket fence, are four houses [9 sec]

- The camera is right behind the picket fence. A small alley separates that fence from another one in front of some houses [7 sec]

- As usual, Ozu pulls us closer and closer to the upcoming scene...

- A different alley, looking straight on at a small hill, covered in grass. Characters pass through a dissecting alleyway and at the top of the hill [8 sec]

- Axial cut to a closer position to the hill. Check out the way the ridge of the hill is only visible through a narrow section of frame consisting of the open space between two opposing roofs. We see a man walk by this space, pulling a cart [6 sec]

- The camera is now about halfway up that little hill. Four boys in school uniforms are singing and walking [14 sec] ... the scene begins.

- The boys sneak away to watch television at the beatniks’ house. Like Equinox Flower, this film is filled with red at the edged and backgrounds of the frame.

- The beatniks have two cool movie posters on the wall. First, we see Louis Malle’s Les Amants (The Lovers) [1958] and then Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones [1958]. They are definitely hip.

- Ozu always seemed to have such confidence in his child actors — Kôji Shitara (Minoru) and Masahiko Shimazu (Isamu) carry the film. From his early films, he always seemed to be successful at directing kids so that they blended into the very naturalistic film environment which he created.

- In this film, the boys have star billing.

- Shimazu was six going on seven when he made this film. He appeared in three of the next four Ozu films and had a great role as the son of the chauffeur in Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963), his final IMDb credit.

- The mother, the ageless beauty Kuniko Miyake, asks the boys where they’re going; to study English, slays Minoru. She warns; them not to go watch television.

- Minoru, in English: “Of course, madame.”

- Isamu, in English: “I love you.”

- Her response: bakane ...

- 0:15:25: This is the identical joke about an English lesson that first appeared in Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941).

- The fart jokes are so bemusedly detached.

- 0:18:25: Father (Chishû Ryû) comes home on the same train as his sister-in-law, Setsuko Arita (Yoshiko Kuga, Fumiko in Equinox Flower). Her character here in a nice bridge between the kids and adults.

- 0:31:45: Haruko Sugimura is again given the thankless role of playing a bitch. She does it well, especially in a scene like this one, when she tells her mother to “go to Mt. Narayama where the old go to die.” There are two great films on the subject: Criterion’s Ballad of Narayama (1958) [Spine #645], directed by Keisuke Kinoshita and Shôhei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama (1983).

We feel like we’re due for a break from all this domestic life, and we get it when the misunderstanding about the dues is cleared up.

The camera is placed in the same position as the penultimate pillow shot from the beginning of the film. The women disappear back into their houses and Ozu holds on the empty space for a moment / cut / neon; one of our characters walks towards us / cut / sign: “Ukiyo Restaurant.”

In the bar, Eijirô Tôno (Tomizawa) is sitting in the background. Ryu eventually comes in and asks if he had left his gloves. He starts to leave when Tomizawa calls him over and they share a few drinks and some brief conversation. Tomizawa is depressed about being unemployed and is extremely drunk.

Meanwhile, the kids are rebellling — they want a television set. The scene erupts when Father comes home; in the midst of the argument, Minoru makes a speech, driving home the point of the film, and helping us to understand the ironic nature of its title, Good Morning.

- “I want a TV set.”

- That’s too much talking.”

- So do grownups. ‘Hello,’ ‘good morning,’ ‘good evening,’ ‘a fine day’ ...”

- “Baka!”

- “‘Where to?’ ‘Just a ways,’ ‘Is that so?’ Just a lot of talk. ‘I see, I see.’ Screw that!”

- “Shut up! Be quiet! ... Boys shouldn’t chatter. Be quiet for a while.”

This, of course, leads to the boys not speaking to anyone but each other. No talking, but “farting is okay.”

- 0:59:22: Trying to get lunch money via pantomime. First Isamu, then Minoru try to explain I to the adults without words. Setsuko tries to translate: “The firemen put out the fire, you gave them tea and you paid them.”

- 1:05:17: Setsuko is explaining to Heiichirô (Keiji Sada) about the kids not talking. Their conversation as superficial as Minoru described, but one can tell that there is an underlying affection between the two.

- 1:06:21: Keitarô (Father) is in a bar. “Someone said TV would produce 100 million idiots.” Published in 2006, “A Nation of One Hundred Million Idiots? — A Social History of Japanese Television, 1953-1973” this volume treats the subject in great depth.

- 1:08:14: Tomizawa, drunk, coming home to the wrong house.

- 1:11:39: Things tourn dark when Mother wonder if maybe she shouldn’t put some rat poison on the pumice stones that the boys are secretly eating.

The school teacher has come to the Hayashi home to ask why the boys won’t talk; the boys run away; a sober Tomizawa has a new job selling electronics; perhaps father feels a little guilty for his severity towards his sons.

We see the kids running away from the policeman, leaving the rice pot and tea kettle behind. Soon the anxious adults begin searching for them. We see the pot and kettle in a close-up / then in the background of a medium shot, where we see the policeman eating noodles. As they search, Ozu teases the time shots of various clocks: 8:09, 8:46 and 8:49, when Setsuko returns home with the rice pot and tea kettle.

This spurs Keitarô into action. He is going to look for the kids, just as Heiichirô returns with the boys, safe and sound.

- 1:27:34: Remember the guy pulling the cart at the beginning? Same shot, same camera position — this time the guy is moving left to right ...

Film Rating (0-60):

56

The Extras2000 DVD

The Booklet

DVD: Four-page wraparound featuring an essay by Rick Prelinger.

Blu-ray: 12-page wraparound. The first thing you notice are the gorgeous illustrations by Tatsura Kiuchi, on both the box and insert. The essay by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum is brilliant. For example:

“Part of the unexpected brilliance of Good Morning, for example, is how much formal ingenuity Ozu can exercise with visual rhymes in the riotous colors and identical square shapes (on quilts, other furnishings, clothes) of his scenic design, as if to refute or at least complicate the seeming monotony and replications of suburban neighborhoods.”

Since this Blu-ray contains I Was Born, But . . . (1932) {Eclipse Series 1}, Rosenbaum takes the opportunity to compare and contrast the two films, especially the difference between the pre- and postwar “Father” characters.

Commentary

None, unfortunately.

Silent film

None, unfortunately.

Silent film

I Was Born, But . . . (1932) {Eclipse Series 1}, Ozu’s silent comedy, with a 2008 score by Donald Sosin.

Video interview

With film scholar David Bordwell.

Video essay

On Ozu’s use of humor by critic David Cairns.

Film fragment

From A Straightforward Boy, a 1929 silent.

Extras Rating (0-40):

Video essay

On Ozu’s use of humor by critic David Cairns.

Film fragment

From A Straightforward Boy, a 1929 silent.

Extras Rating (0-40):

Comments

Post a Comment